The Citgo gas station on Martin Luther King Drive in Adamsville, a neighborhood in western Atlanta, has been a community staple for fuel and snacks for more than three decades. But over the past few years, the store has become a hotspot for crime in the area. In 2022, it’s gotten out of hand.

Between January and August, the Adamsville police department was dispatched to the station 98 times for reasons including open drug sales in the parking lot, prostitution and even someone being shot to death.

“It’s been like a war zone,” said Andrea Boone, the Atlanta City Council member representing District 10, which includes Adamsville. “No one buys gas from this store anymore. It’s the worst gas station in Atlanta.”

Crime is a regular occurrence at gas stations and c-stores, and not just at the mom and pops of the world. Last October, a group of armed men robbed three 7-Eleven convenience stores in downtown Chicago in a span of 30 minutes. In August, a man was shot at a Circle K in Phoenix, while another was shot multiple times outside an EG America-owned Loaf ‘N Jug in Colorado Springs.

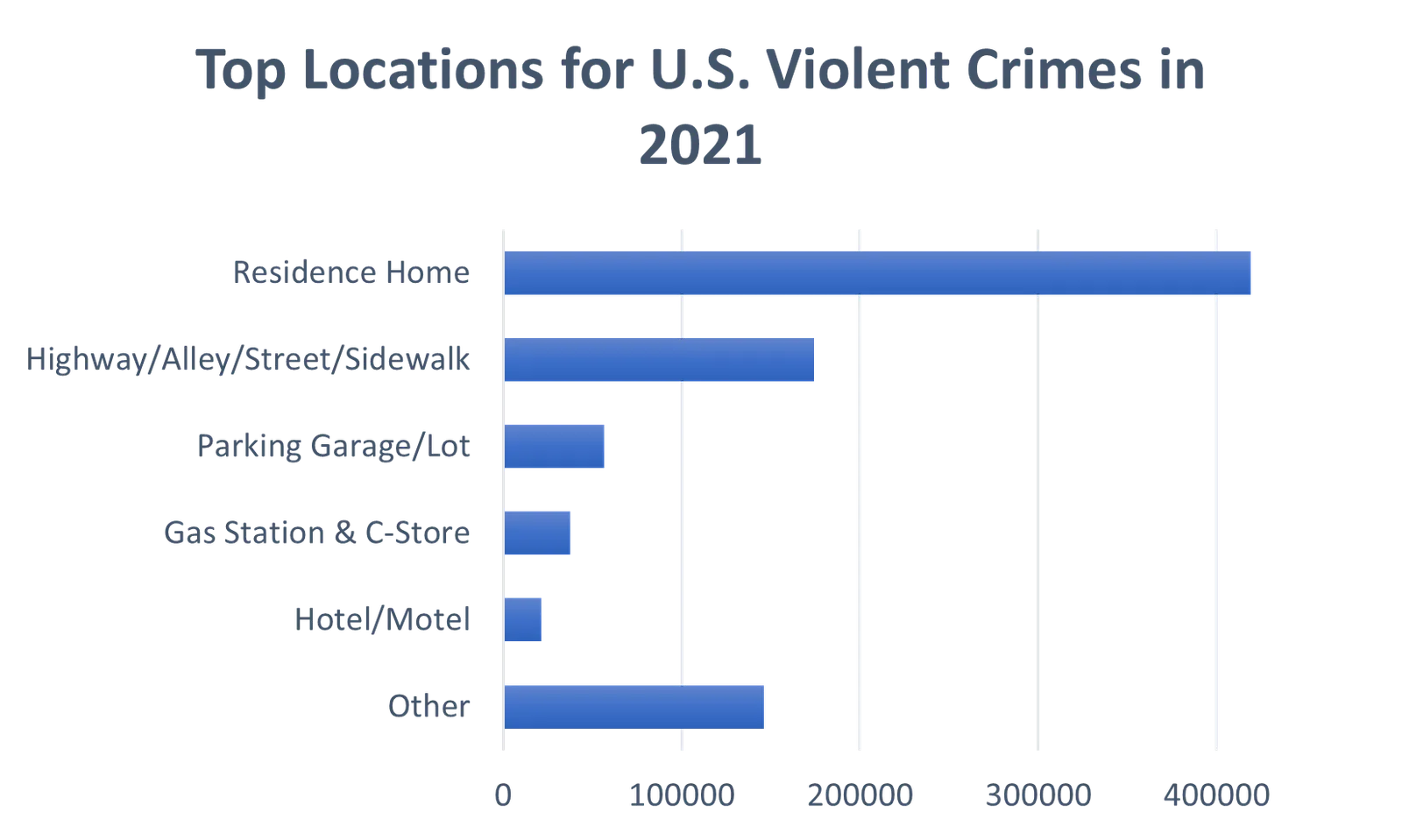

In 2021, gas stations and c-stores had a combined 37,561 violent criminal offenses reported to the FBI — equating to over 5% of the country’s overall violent crimes that year, according to the FBI’s most updated Law Enforcement Data Explorer. Between 2011 and 2021, c-stores and gas stations had a combined 202,552 violent criminal offenses reported, also equating to over 5% of violent crimes in the U.S. during the decade.

The crime happening at the Adamsville Citgo station has reached a critical level and needs immediate attention, Boone said. Boone and others from the Adamsville community joined a nuisance hearing in the Atlanta Municipal Court Aug. 19, laying out their case to shut down the store and station. The ruling is expected to be heard this fall, and if the site remains open, it needs security and new ownership that respects the community, Boone said.

“We need to send a message to others who want to use the city of Atlanta as a place of criminal activity — it will not be tolerated,” Boone said. “Crime is not welcome in our neighborhood.”

Convenient for customers, convenient for criminals

C-stores and gas stations are a hotspot for crime for many reasons, one of which being their small, low-staffed setup.

“C-stores’ small format is convenient for customers but convenient for criminals as well,” said Karl Langhorst, former senior director of loss prevention for Kroger’s previously owned convenience division. “Easy in, easy out.”

Anthony Perrine, owner of family-operated, Kenosha, Wisconsin-based Lou Perrine’s Gas & Grocery, agrees that c-stores’ small and quick format makes them an easier target for criminals. He also notes that c-stores’ typical large parking lots attract suspicious activity as well.

“C-stores have such a high in and out rate, it’s a great spot to do illegal things because you’ll look less conspicuous,” he said. “Big parking lots by nature — that’s why they draw in crowds.”

The fact that c-stores hold lots of cash also makes them susceptible to crime, said Wade Horton, director of Pinkerton, a corporate risk management services firm that works with c-stores and other retailers. And so do their long hours of operation into the night and their location, he said.

“[C-stores] are generally located off of sidewalks and roadways, which makes for easy access and escape,” he said.

Perrine agrees that location is a big factor in c-store crime — and it’s an uphill battle to face for most.

“If you’re not in a rich area or off a highway, good f***ing luck,” he said.

Battling organized retail theft

The prostitution, gun violence and drug deals happening at the Adamsville Citgo station are not necessarily the norm. Most often, c-stores deal with shoplifting and armed robbery — which are surging in some parts of the country.

In Baltimore, convenience-store robberies saw a 514% increase in February 2022 compared to the previous 52 weeks, according to the Baltimore Police Department. By March, the city had experienced “at least 86 convenience store robberies” — a far cry from the 14 in the same span of 2021.

Getting robbed is always the top concern for c-stores, Perrine said. C-store robberies are so common that they’re even portrayed in video games.

“You play Grand Theft Auto, the easiest way to get money is to rob a c-store.” he said. “It’s easier to hit a c-store than a bank.”

Beyond one-off robberies and cases of shoplifting, c-stores face an escalating challenge — and potentially lots more money lost — from organized retail theft. Unlike standard theft, which usually involves individuals stealing from the store, organized retail theft includes groups of people part of criminal rings with the intent to sell and distribute stolen merchandise, according to the California Department of Justice.

Since organized retail theft is done for resale, thieves usually target popular, expensive items to steal in mass quantities. In c-stores, that could be something like beef jerky, Langhorn said.

“We’re talking groups focused on c-stores for this, since it’s so easy to go in and steal from them,” he said.

Organized retail theft is a felony and poses a threat to not just c-stores, but all retailers, Langhorn said. Although it varies by industry, in general, organized retail crime costs retailers an average of $700,000 per $1 billion in sales, according to the National Retail Federation’s 2020 Organized Retail Crime Survey.

“Shoplifting has been around since the first retailer opened their doors, and depending on the amount stolen, it typically won’t put a retailer out of business,” Langhorn said. “But organized retail theft is prevalent and continues to grow across our country.”

Better lighting, more cameras

There are steps operators can take to ensure the safety of their staff and customers, experts say. And they begin in the forecourt.

“Anyone in crime prevention will tell you crime prevention starts outside of the store,” Langhorn said.

C-store operators should ensure there’s good lighting on the forecourt at all times and that the exterior of the store is presentable — meaning the building is free of any damage or vandalization, Langhorn said. Not having these standards in place can yield an environment that’s inviting for criminals, he said.

Horton agrees that the store’s appearance goes a long way in preventing crime, referencing something he calls the “broken window theory.”

“If something looks run down, crime is more likely to occur,” he said. “A single store operator on a dark street will probably see an increase [in crime] than one on the corner of two major highways with major lighting.”

Langhorn also notes keeping the windows clear of obstruction is important, since blocked windows can help criminals once they’re in the store.

“C-stores market their specials on the windows, but at the same time, it blocks the view,” he said.

One way to utilize signage is to have signs that say what crime-prevention measurements the store takes, Langhorn said. This can be a poster on the window saying there are cameras in and around the site or a sign that tells the public that the store uses a drop safe to store their cash.

“If robbers know a drop safe is in there, there’s typically less of an appetite,” he said. “If they know the store has quality cameras and know they could be caught on video, it’s an element that they avoid.”

Circle K uses security cameras throughout each store’s premises to protect against theft, property damage and credit card fraud at the pump, the company has said. The chain also uses anonymous video analytics, which uses pattern detection algorithms to scan real time video feeds, allowing it to track the number of individuals in its stores and consider certain demographic information without identifying them. In select stores, Circle K also uses video cameras and sensors to map individuals’ movements and identify what items they take as it tests frictionless checkout technologies.

Since revamping its safety and security measures in 2018, 7-Eleven has used internet protocol (IP) surveillance cameras — cameras that receive and send video footage via an IP network — in and around its stores. 7-Eleven has said these cameras help it capture events as they happen, collect data to understand who is coming and going, gain information to share with law enforcement and help identify robbers by capturing information from the electronics they’re carrying during a crime.

Yet simply having cameras inside and outside the store isn’t enough. C-store operators should have around-the-clock access to their cameras for when they’re off site, said Perrine, who monitors the 32 cameras for his 4,000 square-foot store 24 hours a day.

“I have access to [the cameras] on my TV at home, constantly checking in, constantly being around,” he said. “If you don’t have access to your cameras 24/7, that’s an issue.”

But while having around-the-clock access to cameras in and around the store is a big help, they aren’t the end-all-be-all to ending crime, Horton said.

“Cameras result in arrests if something occurs and removes repeat offenders, but they don’t prevent anything,” he said. “Cameras don’t deter crime — they just document it.”

A safety-first culture

Beyond cameras, c-store operators can invest in security guards for extra protection.

In 2018, QuikTrip hired its first set of armed security personnel as a response to a surge in crime in its home city of Tulsa, Oklahoma. According to a local news report, having the guards on site significantly decreased thefts and other incidents at QuikTrip's Tulsa stores.

Today, QuikTrip has guards — called division protective service specialists — in all of its cities of operation. The guards’ main priorities are to protect employees, customers and the property from harm; and to deter illegal activity, like theft and vandalism in and around QuikTrip’s stores.

By 2020, Perrine had security working at his store during weekend evenings to deter large crowds. When business slowed once the pandemic hit, he let them go. However, it didn’t take long for him to bring them back, which he did during the unrest in the aftermath of the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha.

Despite the benefits of on-site security, hiring guards may not be feasible for many c-stores amid a tight labor market. That’s why training current employees on how to handle potentially dangerous scenarios is essential, Horton said.

“It’s hard to tell people to add more staff,” he said. “But having a well-trained staff on how to handle situations goes a long way.”

This starts with employee awareness — educating team members on the potential for certain crimes and response procedures to said crimes, Horton said. For example, in a robbery, staff should know that once a robber is leaving, don’t try to stop them, since it may cause more conflict, he said.

“Make employees aware on day one of onboarding that they can face these things and how they should react,” he said.

Working with local law enforcement can be a form of security for c-store operators seeking extra protection. In fact, some cities even require it.

In Houston, every c-store is required to register with the Houston Police Department (HPD) to improve data tracking concerning crimes around convenience stores. The HPD also requires c-stores take an online security training course and meet a variety of conditions, ranging from having surveillance cameras throughout the store to installing panic buttons at the cash register.

Partnering with law enforcement not only helps c-store operators from a safety and education standpoint, but also creates operational efficiencies for the police department, Langhorst said.

“Law enforcement doesn’t want [911] calls,” he said. “They’d rather come in and make recommendations, like making the outside clean or investing in cameras and security.”

Besides working with law enforcement on crime prevention training and strategies, c-stores can request to have off-duty police officers sit in their parking lot and monitor the store for extended periods of time. Since officers can make arrests on the spot if needed — and aren’t being paid by c-store owners — this is more effective than hiring a security guard, Horton said. It’s also a great way to build a relationship with the local police department.

“Offer police free coffee, have [the store] be a place where they drive through and monitor,” Horton said. “It goes a long way.”

Although many regional and national c-store chains have developed crime prevention measures in recent years, unfortunately, much of the industry focuses more on merchandising and sales than crime prevention, Langhorst said.

“There’s a long way to go — and the challenge isn’t getting any easier,” he said. [C-store operators] have got to be as forward thinking with criminal activity as they are with getting customers into the store.”

This type of thinking comes down to creating a safety-first culture, he said.

“At the end of the day, you've got to develop a culture, whether you own a couple or a couple hundred stores,” Langhorst said. “C-store owners have got to take the mindset of ‘Everything I do, consider the safety and security of team members and customers.’”